What are some fundamentals of Java beyond what the classroom might show? Not the normal stuff like syntax, data types, classes, or even OOP concepts like classes and polymorphism. I’m talking about concepts that we can take into an enterprise environment to form a baseline understanding of what to do and where to go.

Table of Contents

- Basics

- [[#Basics#Packages|Packages]]

- [[#Basics#Collections|Collections]]

- [[#Basics#Access Specifiers|Access Specifiers]]

- [[#Basics#Exceptions|Exceptions]]

- [[#Basics#Annotations|Annotations]]

- [[#Basics#Last-Minute Tidbits|Last-Minute Tidbits]]

- Functional Programming

- More Advanced

- [[#More Advanced#Dependency Injection|Dependency Injection]]

- [[#More Advanced#Testing (JUnit)|Testing (JUnit)]]

- [[#More Advanced#Maven/Gradle|Maven/Gradle]]

Basics

Packages

Want to use a package? Import it! …or don’t?

import com.example.geometry.shapes.Circle; // Get the `Circle` class

import com.example.geometry.shapes.*; // Actually, get all classes

com.example.myproject.MyClass obj = new com.example.myproject.MyClass(); // No import neededEvery Java program imports

java.langimplicitly, allowing use ofString,System,Math, and alike.

Want to create a package? Sure, just add package com.domain.project.class then compile it with javac -d <directory> <javafilename>.

Collections

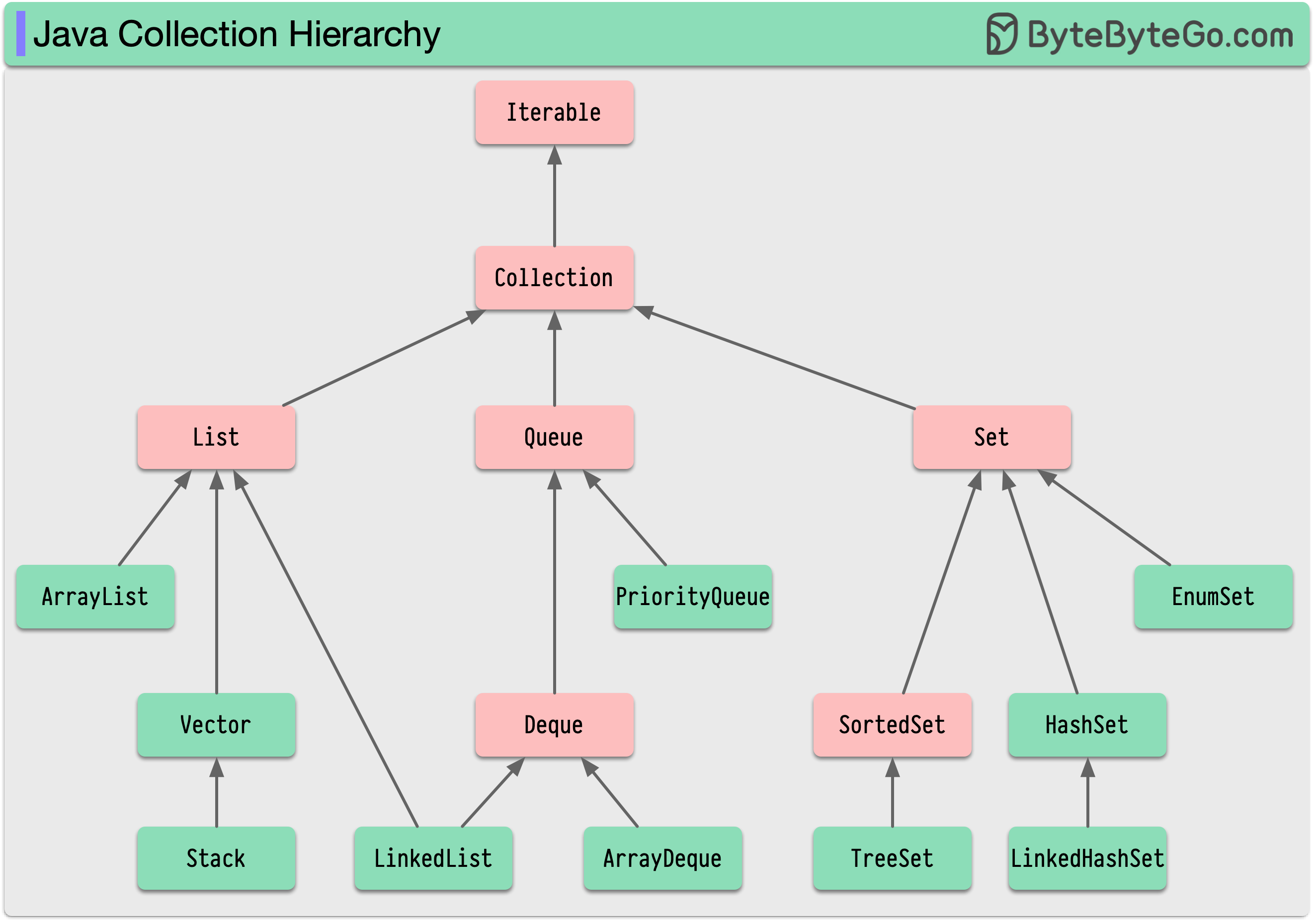

Mostly intuitive, but it helps to recognize the hierarchy between these collections. In the following diagram, red indicates an interface. Most don’t realize at first that a LinkedList is a Queue.

Access Specifiers

| Modifier | Accessible From | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

public | Everywhere (any class, any package) | API methods, entry points |

protected | Same package or subclasses (even in other packages) | Inheritance, subclass customization |

| (default) (no modifier) | Same package only | Package-internal utilities |

private | Only within the same class | Encapsulation, hiding internal state |

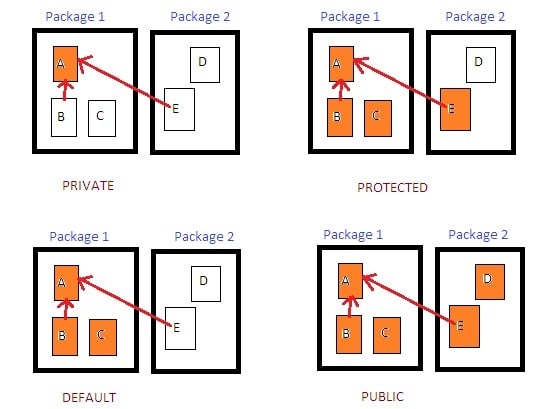

| This is a great visualization each access-specifier assigned to a member in Class A and who can access it—with arrows pointing at parent classes: | ||

|

Exceptions

- Checked Exception: Checked at compile time (e.g. IOException).

- Unchecked Exception: Checked at run time (e.g. NullPointerException).

- Error: Irrecoverable (e.g. OutOfMemoryError).

Annotations

You’ve probably seen things like @Override, @Test, @Deprecated, and @SuppressWarnings("unchecked"). Annotations are not logic, but metadata for use by the compiler.

This generally is not a topic that needs studying since it is used and understood at the user-level, provided by documentation for whatever tool/framework you need to use. We need not concern ourself with the mechanism behind it for a basic understanding.

Last-Minute Tidbits

Some ideas might be not-so-obvious:

- A static method doesn’t need an instantiated object to be called, we can just directly call it on the class.

- A

finalclass cannot be subclassed.

Functional Programming

Java 8 added modern functional programming features like lambda expressions, higher order functions (Streams API), and method references.

Lambda Expressions

Like most languages, syntactically written like (parameters) -> expression, or (parameters) -> { statement1; statement2; }. They are intrinsically linked to functional interfaces—an interface with only one method that needs to be implemented. Java provides a lot of common ones you might know.

Predicate<T>: Returns a boolean, you’re probably going to see this in a.filter().- Example:

Predicate<Integer> isEven = n -> n % 2 == 0;now runisEven.test(4)and see that it returns true..

- Example:

Consumer<T>: Returns void, great for side effects.- Example:

Consumer<String> printUpperCase = s -> System.out.println(s.toUpperCase());and callprintUpperCase.accept("hello");to see it printed.

- Example:

Supplier<T>: Returns type T without any arguments, great for a useful random value.Function<T, R>: Returns typeRgiven an input of typeT, representing a transformation of data.

Method References

A shorthand for a lambda that just calls an existing method. Math::abs expands to x -> Math.abs(x).

public class Utils {

public static boolean isEven(int x) { return x % 2 == 0; }

}

List<Integer> numbers = List.of(1,2,3,4,5);

numbers.stream()

.filter(Utils::isEven) // method reference

.forEach(System.out::println);Higher-order Functions (Streams API)

Import via java.util.stream.

.stream() is commonly found on Collection interfaces like List, Set, Queue and converts it into a Stream object. A Stream has a variety of higher-order functions, notably filter, map, reduce, min, max, sorted, etc.

Don’t forget, you’re left with a Stream now, so what you do next can’t work as if you had the original List (as an example). You can continue processing with things like .foreach() to iterate over the stream or use terminal operations to produce a result. Alternatively, you can collect it back into a List with .collect(Collectors.toList()).

More Advanced

Dependency Injection

More of a general programming construct, but refers to minimizing tightly-coupled code. Rather than having a class create a dependency (i.e. object) needed to run, it’s provided from outside. This concept is not to be confused with literal package dependencies.

A classic example is constructor injection:

class BankingService {}

class PayrollSystem {

private _BankingService: BankingService;

constructor(aBankingService: BankingService) {

if (!aBankingService) {

throw new Error('Never allow a null!')

}

this._BankingService = aBankingService;

}

}Here, whoever constructs PayrollSystem must create the BankingService and pass it down rather than have PayrollSystem create it (tightly coupled).

What if we didn’t do this, and PayrollSystem created BankingService instead? Imagine we have a MockBankingService for testing, we won’t be able to inject it, we’re limited to what we’ve written.

| Tight Coupling (No DI) | Shallow Coupling (DI) |

|---|---|

| PayrollSystem └── new BankingService() └── new HttpClient() └── new SSLProvider() | CompositionRoot (main program) ├── create HttpClient ├── create BankingService(HttpClient) ├── create PayrollSystem(BankingService) |

| A mild comparison: Imagine you have a React button component; it would be silly to make 3 separate components just because each one uses a different click handler—passing it as a prop fixes this. Realistically, it doesn’t have to be 3 different buttons, it can be just one, but the act of injecting the click handler reduces coupling especially if the behavior could change. |

Constructor injection is not the only method! You can directly set public fields, use a setter method, or take a look at property/method injection.

Conclusion: This is a simple topic that can be difficult to wrap your head around unless you start looking for it, and begin developing that intuition. Try programming a few programming exercises converting a poor implementation to one with dependency injection.

Testing (JUnit)

- JUnit is annotation-based, e.g.

@Testmarks a method as a test,@Tagcan mark/filter for certain tests,@BeforeEach/@AfterEachto mark a method to run before/after each test method in the class, etc. - Assertions determine success, e.g. use

assertEquals(expected, actual),assertThrows(...),assertTrue(...), etc. - Test (method) naming should describe behavior, e.g.

throwsWhenDivideByZero(). - Parameterized tests allow running the same test on multiple inputs via

@ParameterizedTest+@ValueSource(...).

You’ll need the JUnit package—for Maven it is:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.junit.jupiter</groupId>

<artifactId>junit-jupiter</artifactId>

<version>5.x.x</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>Import with:

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.*;For more realistic scenarios, you may want to start simulating larger dependencies like databases, APIs, and other services without messing with the real thing. This is where something like Mockito can come into play.

For Spring Boot, you’ll find that it extends JUnit and Mockito.

Maven/Gradle

These are both build automation and dependency management tools; standardizing project structure, and coordinating plugins to maintain a complex project. Maven depends on a pom.xml config, whereas Gradle uses a build.gradle config. Generally speaking, Gradle is considered modern, harder to master, more flexible, and faster than Maven—the most likely enterprise standard for older projects.

Maven Project Structure (Convention)

myapp/

├─ src/

│ ├─ main/java/ (your code)

│ ├─ main/resources/ (config files)

│ ├─ test/java/ (unit tests)

├─ pom.xml (Maven config)

Maven Config

Defines project metadata like name, version; dependencies (libraries); and plugins in the form of an .xml file.

Maven Core Commands

mvn clean- delete compiled outputmvn compile- compile source codemvn test- run unit testsmvn package- into a.jaror.warmvn installmvn spring-boot:run